What follows is a recap of my MAA Retiring President’s Address. It contains some slides, all the lessons, and hints at the proofs for identities. The drawings are my own.

The title of my talk has its origins at a previous MathFest. Twenty years ago, I was invited to speak in Boulder, Colorado. This is the title slide from that talk.

“Proofs That Really Count” also coincided with the title of a book co-written with my dear friend Art Benjamin, released at the same time. I did not get to travel to Boulder to give the talk because I was 8 ½ months pregnant. But with Art’s help, a camcorder, a VHS player, and a laptop, we made it work.

Part of me was tempted to finally give that original talk at this MathFest. But I learned so much over the last 20 years, especially as president of MAA, that the presentation definitely needed an update.

Instead, I give you “Lessons that really count.” These lessons are personal, yet I believe they can be applied to life, to mathematics, or to a life in mathematics. I draw on proofs from the original talk to illustrate seven lessons. Expect stories, combinatorial proof, and a whole lot of love for the MAA.

This leads to the first lesson, already illustrated by the example of MathFest 2003.

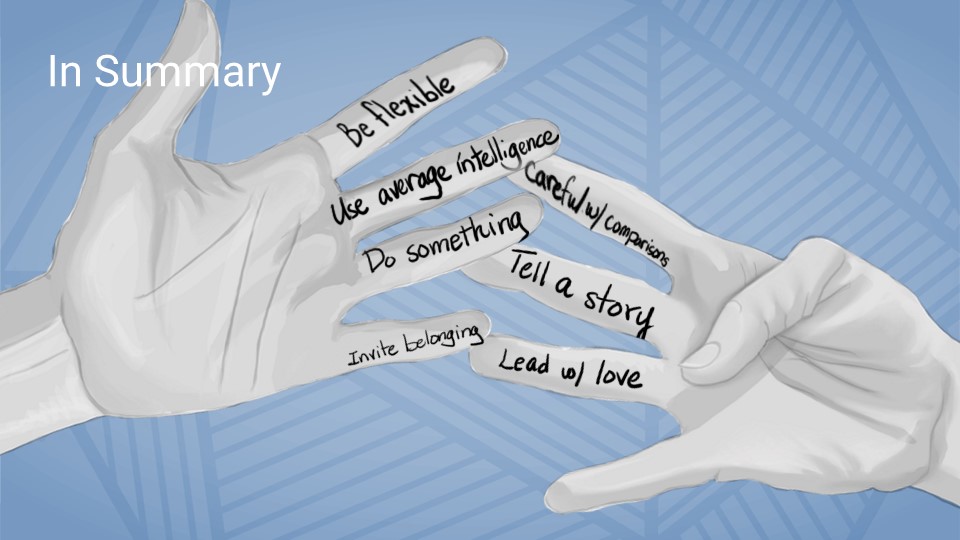

Lesson 1: Be flexible.

I could have given up and withdrawn from the 2003 meeting, Instead I used the resources available to me at the time and found a workable solution. I couldn’t do it alone. I needed help. It required flexibility and support from Art and the MAA. (And I think it was the first remote presentation at a MathFest. It’s not like we had Zoom accounts back then.)

The COVID pandemic required flexibility of all of us. Without much notice, we changed how we worked, how we shopped, what we shopped for, and how we socialized.

It was an externally imposed flexibility and it was exhausting. But there were some positive benefits. COVID social hours reconnected me to old friends and helped me make new ones. Trying to engage “black box” participants forced me to re-examine my teaching practices and intentionally work to increase equity in my classrooms. Removing temptations for academic dishonesty changed by assessment practices. The flexibility needed to deal with the disruption to our lives led to innovations that have carried over to the present time.

What about mathematical flexibility? I imagine everyone has had the experience of trying to solve a problem only to arrive at an impasse. Pólya’s advice from How to Solve It calls directly for flexibility:

If you cannot solve the proposed problem do not let this failure afflict you too much but try to find consolation with some easier success, try to solve first some related problem; then you may find courage to attack your original problem again.

George Pólya

How To Solve It

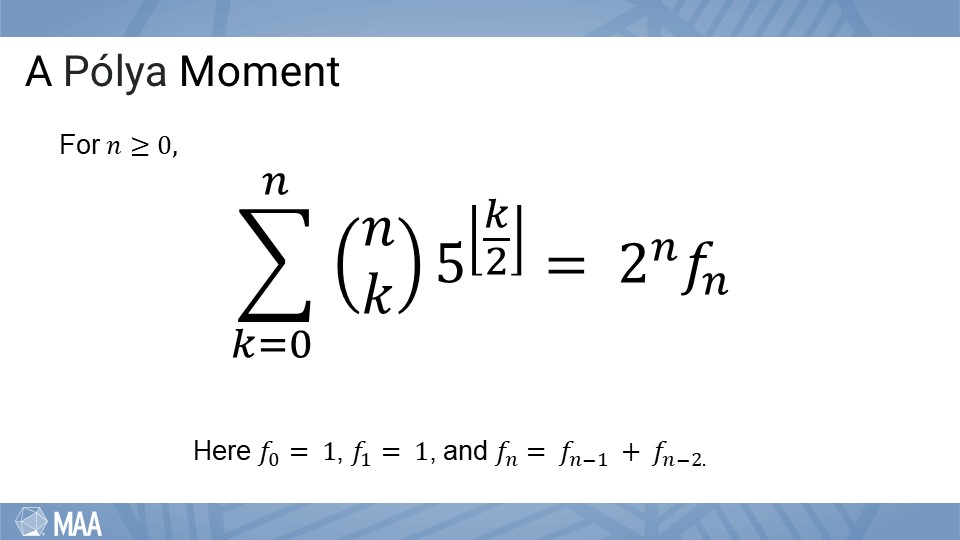

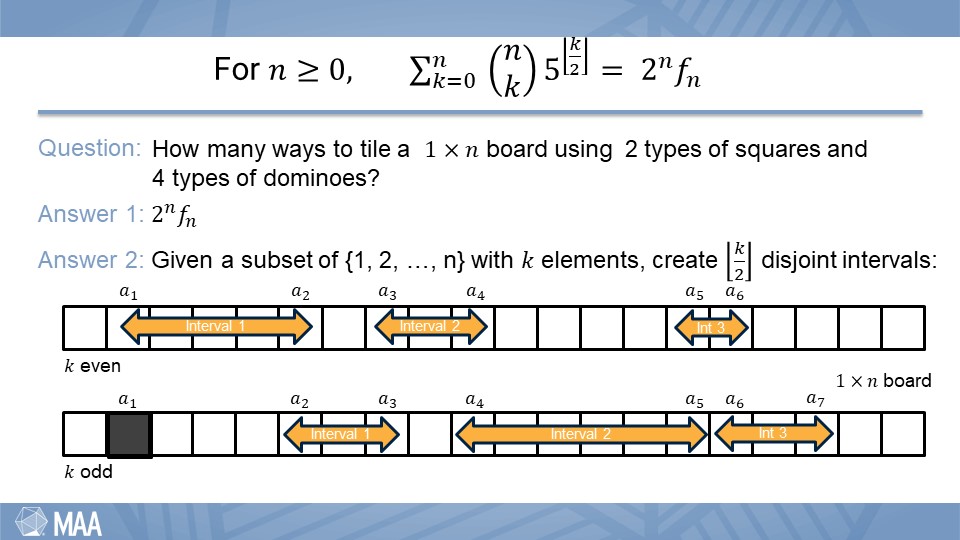

Let’s call such a situation a “Pólya moment”. Art proposed we write an expository paper on combinatorial interpretations of Fibonacci numbers and the punchline would be a combinatorial proof of this identity:

Suffice it to say that we wrote that first paper but did not include the desired identity. Because we hadn’t figured it out …..yet.

Rather than proving the above identity, I proposed a related problem (as suggested by Pólya).

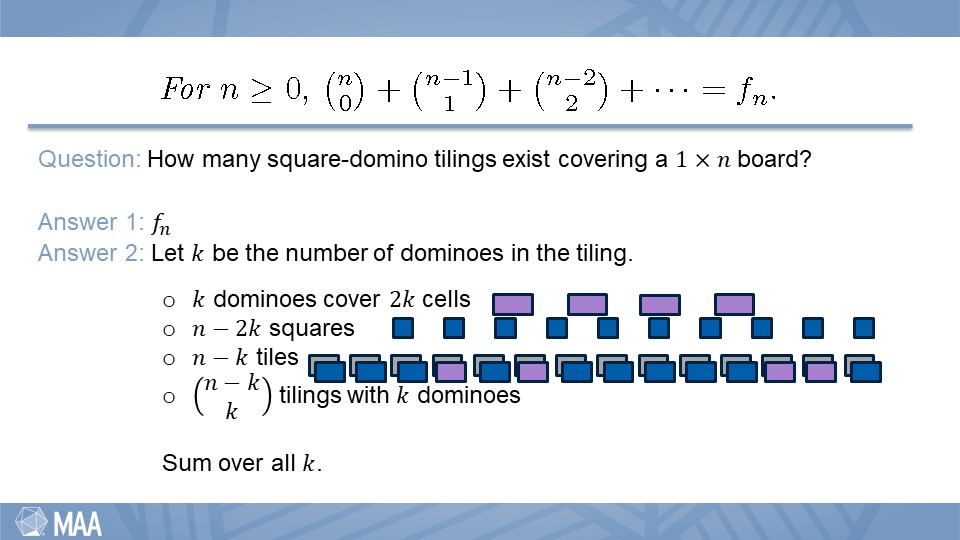

In typical combinatorial proof style, we asked a question and answered it in two different ways. Because the resulting expressions counted the same thing, they must be equal. In general, start with the least complicated side and create an “obvious” question with it as an answer. Try not to overthink it. This brings us to lesson 2.

Emily Puckette, now of University of the South, shared her family wisdom at an honor society induction ceremony at Occidental College back in 2000 (or 2001). “Use average intelligence” was such an interesting turn of phrase. To me it’s a clever way of saying that common sense and hard work can go a long way to reaching your goals (and keeping you out of trouble.) Applied to mathematicians, it dispels the myth of a “math gene” or the idea that mathematicians have to be eccentric geniuses.

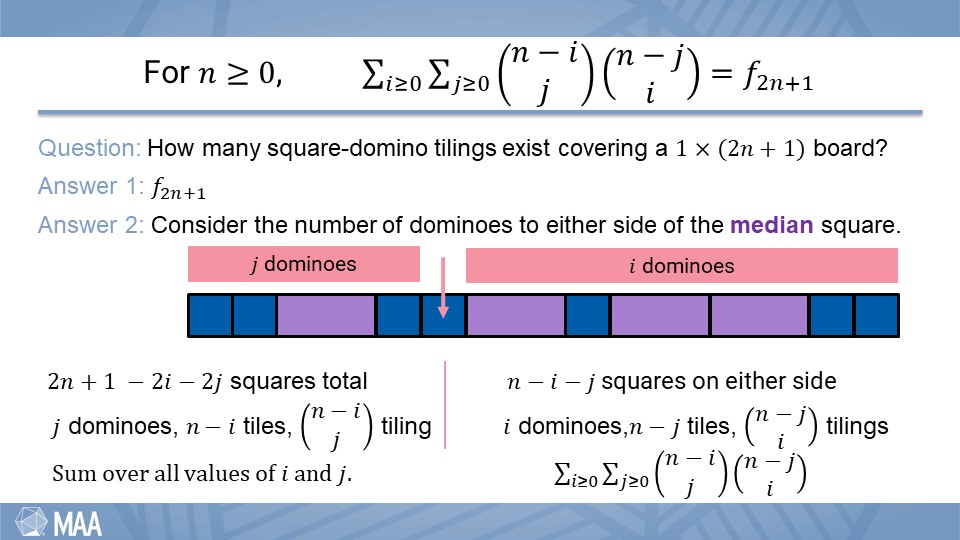

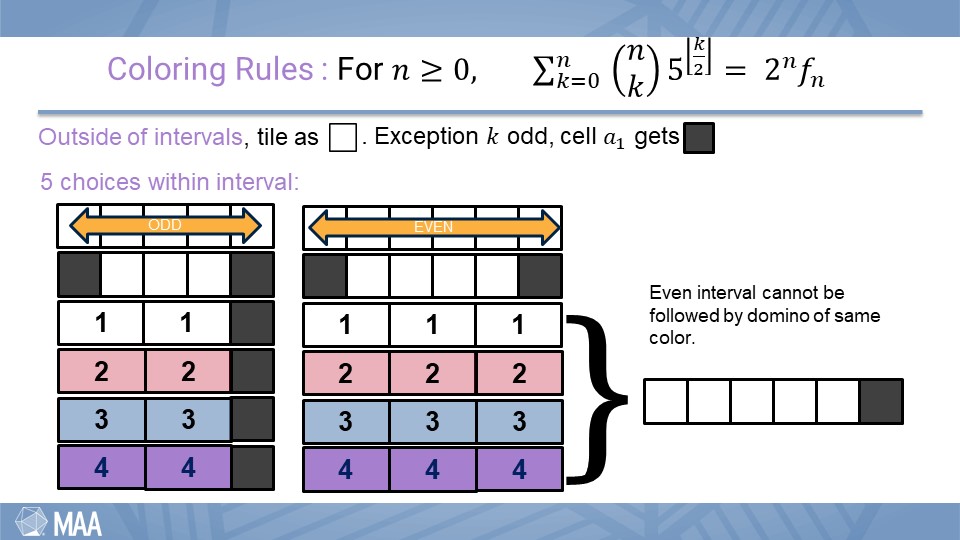

To embrace being average—the next identity used the median as a measure of centrality to combinatorially tackle an identity, similar but more involved than the previous. Rather than a sum of binomial coefficients adding to a Fibonacci number, this time it’s a double sum of a product of binomial coefficients that add to a Fibonacci number.

We used average intelligence two ways here. First we kept the counting question as direct as possible. And we focused on the median square in the second answer to the question. However, “Using average intelligence” might just result in a thought exercise. The next lesson urges us go beyond the cerebral and take action.

Lesson three is simply “Do something”.

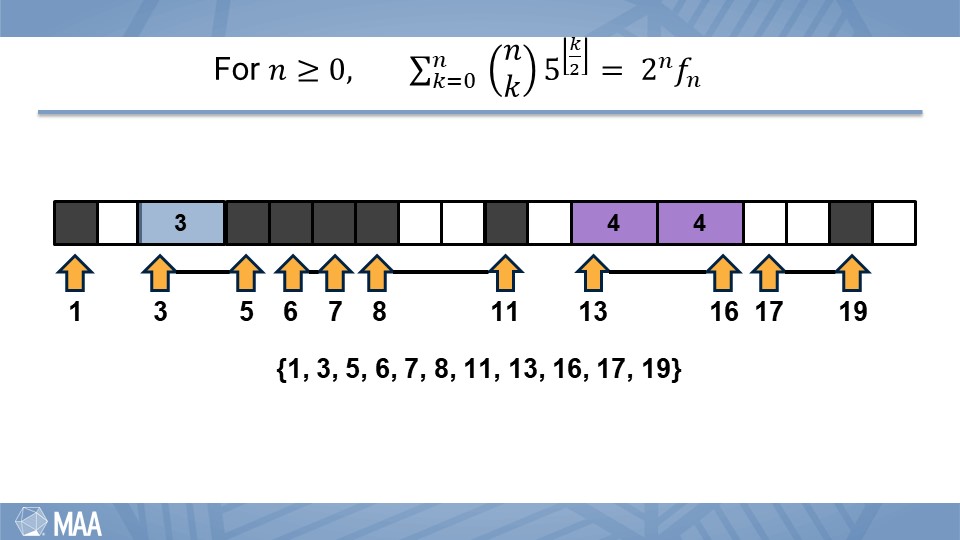

In the spirit of this lesson, we revisited the Pólya moment identity and did something:

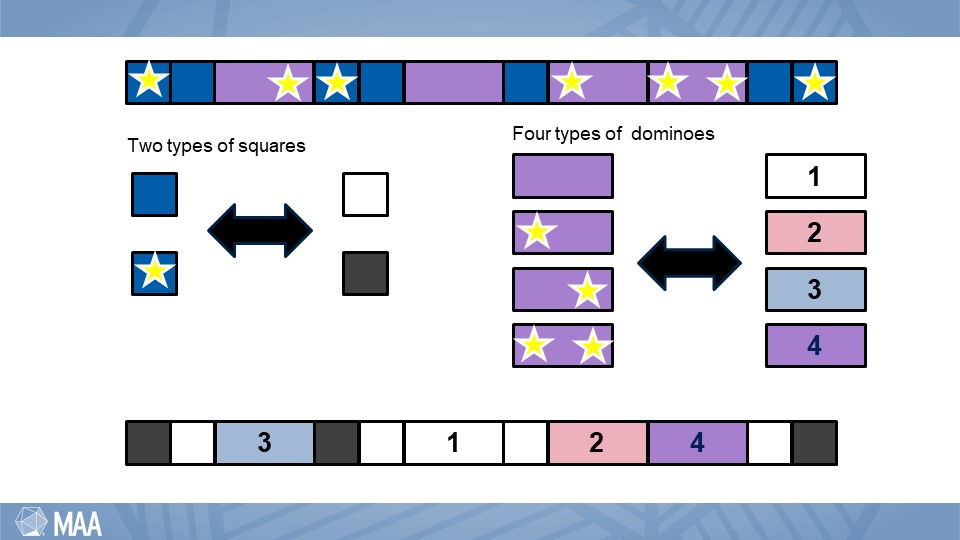

The righthand side counts square-domino tilings of length n where a subset of the n cells is marked (shown above with stars). Having a combinatorial interpretation for one side of the equality means we are halfway done. That was a good start.

It can be surprisingly difficult to start something new—whether it’s a mathematical investigation, a classroom practice, or positive change. Sometimes there isn’t a choice (like during the covid crisis). But other times, a catalyst is needed to get over the energy of activation. The first step to “Doing something” requires at least one of two ingredients: confidence in yourself or trust in your community.

Confidence that you can gain the skills to successfully complete what you start—even if it takes a long time.

Trust that you will be supported to overcome failures and not publicly chastised for them.

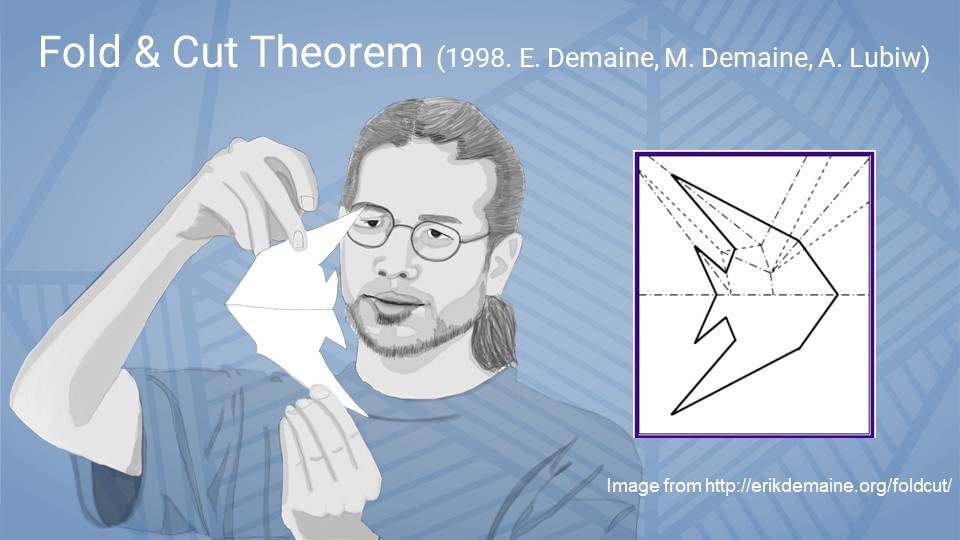

I saw this play out most recently at the MAA NorthEastern Section meeting, held at Fitchburg State University in June. Hema Gopalakrishnan, Sacred Heart University, facilitated a Math Circle Hour for the participants. Working in teams, we tried to fold and cut paper into specified shapes.

You may be familiar with the Fold & Cut Theorem (1998) of Demaine, Demaine, and Lubiw. It asserts any shape created with straight lines can be cut from a single (idealized) sheet of paper by folding it flat and making a single straight cut. We were not challenged with anything nearly as complicated as the angel fish seen here. These were our challenges:

It was fascinating to witness the hesitation of mathematics faculty (myself included) not wanting to start in case our ideas were wrong. In a community of highly educated mathematicians who came together specifically to learn and share, there was a hesitation to engage. I’m sure that the energy of activation is an order of magnitude greater for students in a mathematics classroom. How do we engage our students? By purposefully incorporating equity-based active learning strategies to build confidence… to create community…to develop trust…and to make it easier for them to “do something”.

By inviting people in and valuing their contributions we show them that they belong. When I couldn’t find a quote, I asked ChatGPT to look for me. I think what it presented is a beautiful vision for what the mathematical sciences needs to be (and I hope this is not an AI hallucination.)

The value of belonging was beautifully stated during Allison Lynch’s Alder award presentation. “Building community helps us take on big things.” There are big things that need to be taken on.

Mathematics has a reputation for being exclusive. That has to change.

Mathematics education has become a political hot potato, especially at the K-12 level. That has to change.

Marginalized and low-income students do not persist in STEM classes at the same rate as their more privileged counterparts. That has to change.

Many attendees at this conference, have done more than I can hope to accomplish. People like Aris Winger, Adriana Salerno, Carrie Eaton Diaz, Dan Zaharapol, Deanna Haunsperger, Ron Buckmire and most especially, Dave Kung.

To you I say thank you. I know that I am not doing enough. I do what I can with what I have. One person at a time. One class at a time. One community at a time. I don’t know if I will ever be able to do enough. And that doesn’t feel good. Which leads to the next lesson….

This is my father-in-law, and I can imagine him in the backyard, smoking a cigarette, and sharing his wisdom. “Kid, there will always be someone smarter, richer, or better lookin’.” A firefighter by trade, he could be crude but he was not wrong.

Humans are beautiful, unique individuals. No two are equal. Making comparisons between them perpetuates an unproductive hierarchy.

Alder Award winner Andrea Arauza Rivera, California State East Bay, told a personal story of exclusion during her presentation. She concluded it with the powerful question “Who was I being measured against?” Comparisons between people are harmful.

In the past, I have been known to judge myself as “less than. ” I would apologize for not being “good enough.” Engaging in comparisons made me jealous of those I deemed more capable, more competent, more knowledgeable and did nothing to positively affect my situation.

So I have promised to stop comparing myself to others and to help others (especially my students) do the same. I focus on being my authentic self and work to believe that that is enough. There are plenty of times that I waiver and need external reassurance. Today, I want to personally thank three special mathematicians:

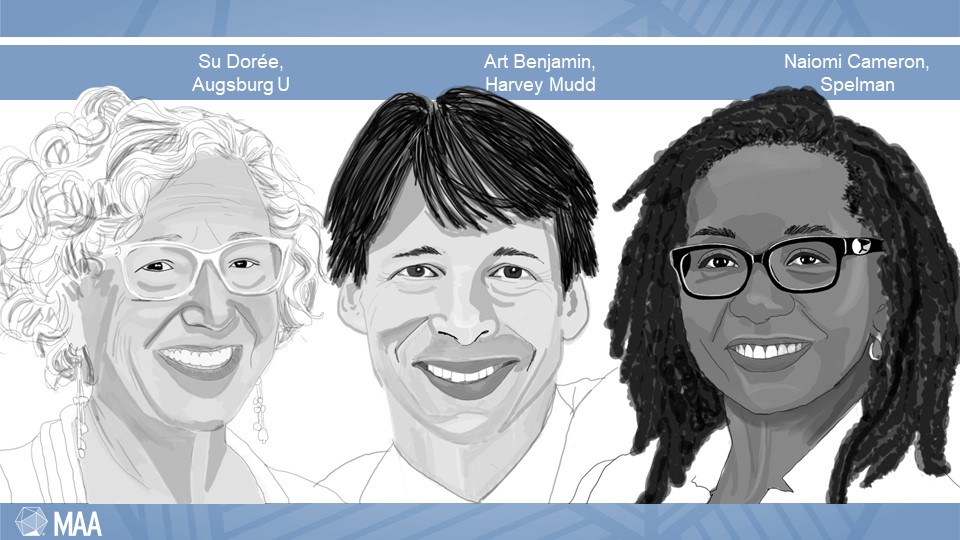

Su Dorée of Augsburg College. Su is the friend who tells it like it is—no holds barred. I can share anything and with great love and respect, she will tell me when I am absolutely wrong.

Art Benjamin, Harvey Mudd College. I can honestly say that I would not be here today, if not for my partnership with Art. He is my co-author, co-editor, and mutual confidante. I often wonder what my life would be if we hadn’t accidentally run into each other at Souplantation in the mid-1990s and finally made plans to get together to talk about math.

Naiomi Cameron, Spelman College, is my COVID buddy. We reconnected during the pandemic and started weekly check-ins. Mostly we explore new-to-us ideas in combinatorial matrix theory. Sometimes we talk associations. Sometimes talk administrations. Sometimes teaching. And always a little bit of math. When I am frustrated with lack of mathematical progress and she redirects us to “writing”. When writing stalls, she suggests new explorations. Naiomi nudges us towards sustained incremental progress. And it works!

I would say that these three people are smarter, richer, and better looking—but in keeping with the lesson, I will simply say, they are beyond compare. I was fortunate to be invited into their lives. Our connections have deepened over the years because of the MAA whether working together in governance, co- editing MAA Math Horizons, or writing for MAA publications. It is the connection to writing that brings us to the penultimate lesson:

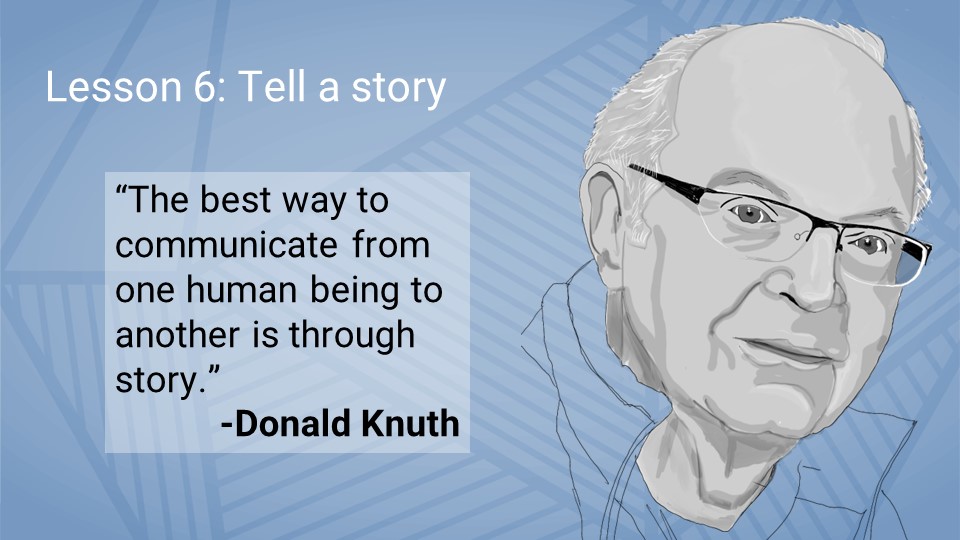

No matter what you are trying to communicate, tell a story.

The best articles—the ones that we really remember and the ones that win awards, capture our attention with a strong hook and they weave tales of mathematical delights. If we want to better promote our subject and invite others in, we must pay special attention to the stories we tell.

In 1967 Linguists Labov and Waletzky, identified a common but surprising structure to simple narratives—forming the foundations of sociolinguistic narrative analysis. They claim when parts of the story are absent, the narrative becomes fragmented and readers get lost. We don’t want our readers to get lost!

I’ve been trying to follow their structure for this talk. Let me illustrate.

- Abstract briefly summarizes the point of the narrative. This my retiring president’s address.

- Orientation sets expectations and ultimate goal. You know there are seven lessons, which will be shared with combinatorial proofs and stories.

- Complicating action is a sequence of actions, turning points, or problems leading up to the point of maximum suspense. There have been several “problems” and I hope you are still excited to see more of the “Pólya moment” identity.

- Evaluation is commentary on the action. It should address why you should continue to care. I have tried to intertwine evaluation with the complicating action throughout.

- Resolution is the attainment of goal and the

- Coda ends the narrative, returning the reader/listener to the present.

The resolution was the completion of the “Pólya moment” identity. I will leave the pictures here. If you are interested in the full details, look at identity 235 in the book Proofs That Really Count.

This identity was introduced to set the stage and illustrate the need for flexibility. It marinated in background as we became more familiar with arguments of combinatorial proof and considered related but more achievable problems. It was then used again to illustrate the idea of “do something” and served as the mathematical resolution. All the while interweaving evaluation in the form of life lessons.

The coda is the final lesson of this story. One that I couldn’t articulate until the end of my presidency. I wrote about it in my final MAA Focus President’s column and I think it bears repeating.

My friend Renée Smith, founder of A Human Workplace, counsels “if you want engagement, stop the fear and love your people.” While she is striving to transform workplace culture, I think her lesson can be applied to mathematics classrooms and communities as well.

Stop the fear. Anxiety and trauma are created in mathematics environments from elementary school through professional communities. Whether a student in a classroom or a professional in a research group, people recoil from being called out as wrong, different, slow, or disappointing. Some take refuge in the excuse “I’m not a math person” and stop trying. Others persist with less enthusiasm and a greater likelihood to refocus energies elsewhere. As a consequence, we lose potential mathematicians and other STEM professionals from the pipeline

Smith wrote, “When we foster a culture of fear, people are so preoccupied by that fear and the physical and psychological toll it takes, so preoccupied figuring out how to survive, that they can’t bring or do their best.” How do we stop the fear? I believe the answer is through love.

I know this sounds naïve, but “love your people” means to care deeply about the individuals in your community, be it a classroom or a boardroom. Take the time to know who your community members are and what they care about. Listen to their dreams.

Creating a loving community is an issue of equity. Feeling acceptance and belonging, promotes support for one another, respectful conversations and respectful conflict, and a willingness to take risks—even as it exposes vulnerabilities. In essence, each person is welcomed and knows they can express their perspective, skills, and humanity without fear. Maybe in the process, they can learn to love themselves and appreciate others a little more.

So, I encourage us to bring our whole selves and our whole hearts to our mathematical lives. Convey more empathy, more understanding, and more respect. Carry less bias, less rigidity, and less indifference. Strive to create a more loving community and keep people engaged with mathematics.

Being President of MAA was a wonderful, unpredictable, and amazing adventure. I have tried to embrace my humanity and lead with love. I love mathematics. I love the MAA. And I will continue to uphold MAA’s vision of a society that values the power and beauty of mathematics and fully realizes its potential to promote human flourishing.

There is nothing inherently mathematical about these lessons. I find them valuable as guides for living and strategies for problem solving. Some space is intentionally left blank for more lessons because I’m still learning.

I was humbled to receive a standing ovation at the conclusion of my talk. Thank you to everyone who attended. It was recorded and will eventually get posted to the MAA member library. I will link it here when it becomes available.

Before I sign off tonight, I want to wish my son Zachary Martin Happy Birthday. He was born 20 years ago today. His arrival was announced in the November 2003 MAA Focus (page 15):

Zachary made my year after returning home from his Math REU this summer when he declared, “Mom, your book was really helpful.” ❤️

Wish I could have been there in person. It is a terrific talk and you were a terrific president. Celebrate! MAA is so lucky to have members like you. Our officers are truly wonderful and I treasure the privilege of their friendships always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This means so much coming from you Martha. Thank you.

LikeLike